I hope everyone enjoyed the latest Society outing - seabound to the Copelands, see Sandra’s report. And if you are interested in local nautical history I would recommend the very interesting exhibition at Mount Stewart House curated by volunteers about the 1895 Mount Stewart Staff Shipwreck. If you haven’t please go and have a look, very well done and a worthy presentation of a very sad story.

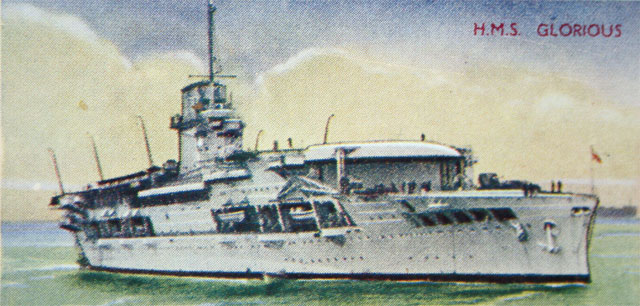

It set me thinking of other seagoing matters with a connection to the Londonderry family and I went back to the launching of HMS Glorious, built by Harland & Wolff. She was ordered by Admiral Fisher as a battlecruiser, laid down in 1915 and launched by Edith, Lady Londonderry in April 1916. The ship took part in the Battle of Heligoland Bight and after the First World War was refitted as one of our largest and fastest aircraft carriers. Unfortunately she was sunk on June 8th, 1940, along with two escorting destroyers Ardent and Acasta, by the German battleship SMS Scharnhost while helping to evacuate aircraft from Norway during the Second World War. Due to communication difficulties between ships, the news of her demise was not known in Britain until announced by Germany, the crew of the Scharnhorst having filmed the battle. Some 1200 men were lost including 43 RAF officers whose experience would have been invaluable during the forthcoming Battle of Britain. Seventeen aircraft were also lost from her decks. HMS Glorious’ ship’s badge, a legacy from when ships had figureheads, portrays a Tudor rose topped with the Naval Crown, motto Explicit Nomen (the name says it all), and I have a lapel version on my gardening hat.

Figureheads were carved in the form of people, beasts or mythological figures in keeping with the spirit or name of the ship. [I think the Glorious and Tudor rose connect through Queen Elizabeth I, nicknamed Gloriana during her reign.] In the early days of seafaring by the Egyptian and Phoenicians the representation of birds and horses was meant to ensure protection from harm. Viking ships had warlike faces and the Ancient Greeks progressed from painting eyes on each side of the bow to boars’ heads signifying ferocity. The Romans had a centurion to represent bravery in battle. A popular lore is that figureheads followed the prevalent anecdotes about sailing in unknown seas. A topless lady was seen as an offering to the gods of the sea to appease stormy weather. However this was contrary to the accepted norm that women aboard vessels was said to be unlucky. Sailors also believed that the songs of mermaids led them to shipwreck on reefs and rocks. The topless lady would distract the ocean gods by her beauty and the ship would be left unharmed to continue its voyage.

The more conservative British ships had clothed women and in the 1700s and 1800s it was de rigueur to have a figurehead, often representing the wealth and standing of the owner. As time went on, the larger and more elaborate figurehead on the bow began to be a problem as the weight of the figure increased the weight of the vessel overall and led to difficulties operating the ship. Elm wood was the first choice but eventually teak, pine and oak were used to reduce the weight. There was also the cost of the carvings, a huge investment in procuring a decent sculpture and the maintenance required. The captains and crew maintained they wanted a figurehead and captains sometimes reached into their own pockets to finance a suitable emblem. For illiterate and uneducated seafarers, the figurehead became the vessel’s pseudonym and the ship came to be identified by the figurehead rather than its actual name. Eventually the carvings became smaller and started being abolished in the 1800s and the buildings of non-wood vessels resulted in the decline of these mascots. The newer vessels were streamlined and there was no obvious place to put a figurehead, whatever size.

During the First World War, British and German ships still carried mascots but the advent of huge battleships resulted in their demise. Smaller Royal Navy ships still carried figures and HMS Rodney was the last battleship to have one. They were replaced by badges linked to the name or role of the ship. Each badge is surmounted by the Naval Crown, a throwback to the Roman practice of giving a crown to the first man who boarded an enemy ship during a naval engagement. Today a ship’s badge shows a little gold artifice representing the sails of a ship and below the emblem and motto adopted by the individual ship, like the Tudor rose of HMS Glorious.

Modern cruise ships sometimes feature old figureheads from day gone by - shown at the right is a photo from Fred Olsen’s Boudicca with the figurehead attached to the forward sun deck.

A great example of a figurehead can be seen on the Cutty Sark, the nickname of Rabbie Burns’ witch Nannie Dee in his 1791 poem Tam O’Shanter. The carving, attributed to Fredrick Hellyer, is white and shows a bare-breasted Nannie holding a horse’s tail. In the poem she wore a linen sark, Scots for a brief petticoat and because it was short it was cutty. Tam O’Shanter’s cry “Weel done Cutty-sark” when he saw her dancing became a well-known catchphrase. The Cutty Sark was a tea clipper, built in Dumbarton in 1869, and you might have spotted her last Sunday on the London Marathon route which passes Greenwich where she is berthed and still doing service as a nautical museum.

Cutty Sark houses the world’s largest collections of figureheads and you might also find some of the more interesting or valuable ones adorning a seaside pub or villa. Or perhaps you will have noticed the statue called Titanica symbolising hope and positive renewal on the plaza of the Titanic Belfast Exhibition Centre, a modern application of the old tradition.